Key takeaways:

1. By looking for existing infrastructure gaps in healthcare, startups can make a difference.

2. Medical entrepreneurs don’t always need science backgrounds. Virtue used her fine arts degree and product design skills.

3. Access to innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems helped her scale.

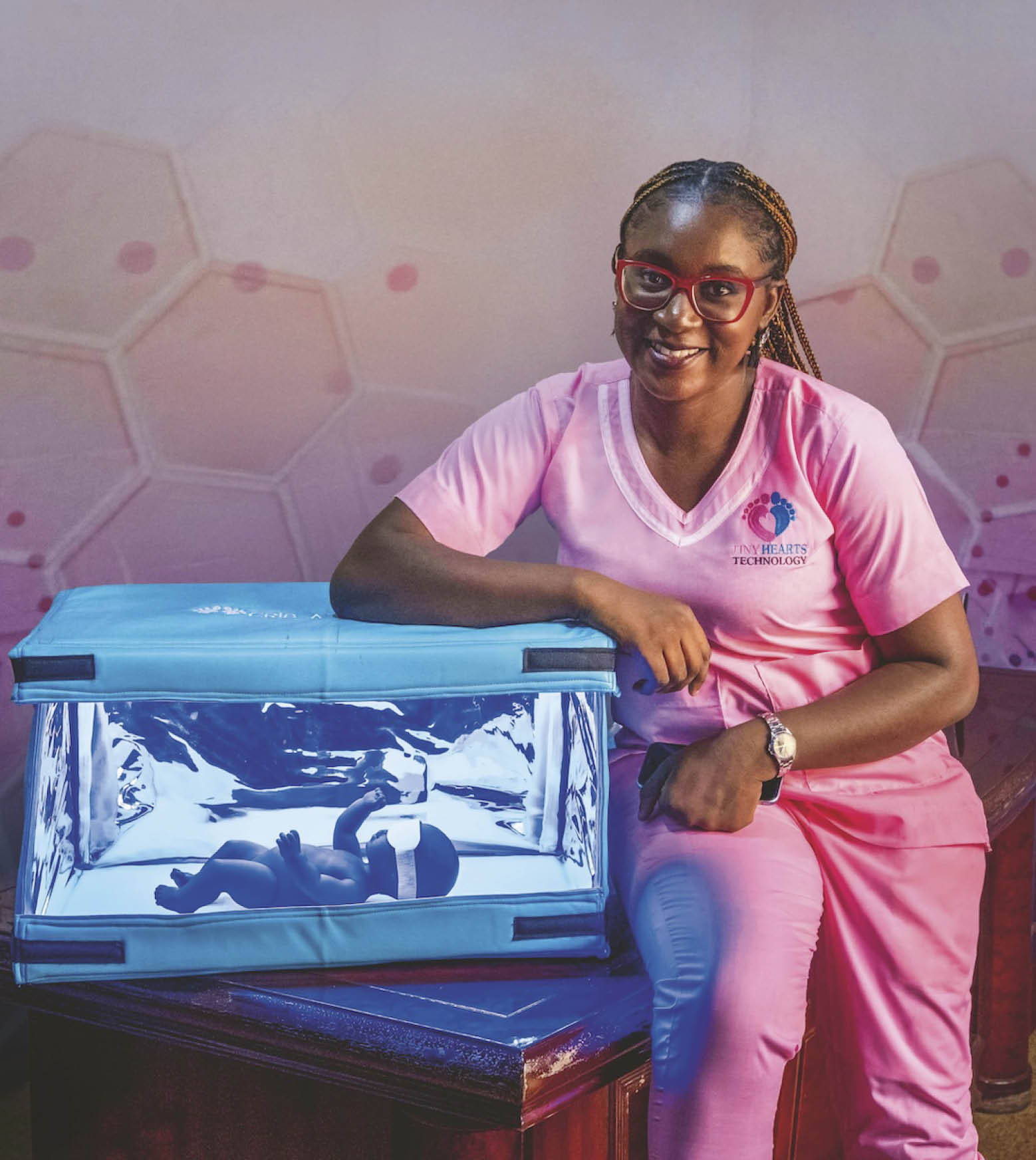

MEET THE NIGERIAN MEDTECH STARTUP SAVING INFANTS' LIVES

Virtue Oboro’s newborn son struggled with severe jaundice in an under-resourced hospital. “I said, you know what, we can do something about this.”

READ TIME: 5 MIN

Key takeaways:

1. By looking for existing infrastructure gaps in healthcare, startups can make a difference.

2. Medical entrepreneurs don’t always need science backgrounds. Virtue used her fine arts degree and product design skills.

3. Access to innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems helped her scale.

“We want to reduce the need to import basic medical devices and improve infant mortality statistics in Africa.”

by the numbers OFFICIALLY Launched in 2018

OVER1.2m babies treated

500 health centres equipped

Retails at USD232 per unit

“We want to reduce the need to import basic medical devices and improve infant mortality statistics in Africa.”

The birth of Virtue Oboro's first child, a son named Tonbra, was a joyful moment, but the family's celebration was short-lived. It became clear that something was wrong with the little boy.

"The day after Tonbra's birth, we noticed how lethargic he was. He didn't want to wake up to feed," Virtue recalls. Her mother, a retired nurse, urged her to take the infant to the hospital. There, doctors diagnosed him with severe neonatal jaundice.

"It's difficult to diagnose jaundice in infants with darker skin," says Virtue. "I thought he had a light skin, like my grandmother, not that he was ill. I didn't know there was a difference between light skin and the typical yellow skin of jaundice."

The diagnosis should have brought relief, but, instead, it marked the beginning of a harrowing ordeal. Tonbra needed an emergency blood transfusion and the hospital didn't have a phototherapy unit available to treat his jaundice. Like many healthcare facilities in Nigeria, the hospital in Ilorin, Kwara State, Virtue's hometown, was under-resourced.

"There was only one phototherapy unit available and the parents of the infant using it claimed it wasn't working, but it was simply not operating efficiently as it needed new lightbulbs," Virtue recalls.

Before Tonbra could use it, Virtue had to buy replacement bulbs herself. Even that wasn't straightforward. "The blue lights are easily confused with those used as a security measure in banks, or those that kill insects, which makes it difficult to select the right ones," she explains.

When the bulbs were finally installed, the hospital experienced power cuts. "Tonbra would receive treatment for a few hours, then the power would go out," says Virtue. The unit also overheated, dehydrating him and causing his skin to flake. "He came down with a fever," says Virtue. "I no longer recognised him."

Researching the problem

The family spent eight anxious days at the hospital, but the trauma – physical, emotional and financial – remained with them long afterwards. Determined to find a better solution for jaundiced infants, Virtue began asking questions and doing her own research.

The need for a solution was urgent. Neonatal jaundice is common among newborns in Nigeria and a significant health challenge. Around 60% of full-term and 80% of pre-term infants experience it. Left untreated, it can cause seizures, hearing loss, vision problems, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and even death.

Although Virtue didn't have a science degree, her degree in fine and applied arts from Nigeria's University of Cross River State gave her a foundation in product design and problem-solving. "I began approaching doctors and asking questions. I could see they were frustrated as they couldn't help their patients effectively under the existing conditions," she says.

Sketching and self-funding a prototype

With her husband, she began sketching ideas and gathering materials for what would eventually become Crib A'Glow – a portable, solar-powered unit using blue LED lights. She wanted the unit to be comfortable, easy to use, and "always on".

She also wanted to design something that didn't look like a cold, clinical device. "I wanted a product that would give parents a sense of solace and control," she says. "We knew what we wanted, but we couldn't identify the right materials for it."

Virtue took Tonbra on 10-hour trips to Lagos to search for better materials. This put more strain on their finances. "We used everything we had for the prototypes and barely had enough to live off because we had to buy materials ourselves and test different solutions."

Joining an innovation hub powers success

A turning point came when Virtue joined the GE Lagos Garage programme – a high-tech innovation hub launched by General Electric in 2016. This gave her access to equipment such as 3D printers and laser cutters.

Then, in 2017, she won the Diamond Bank Building Entrepreneurs Today Award that entailed a USD8 500 cash prize. This financial injection revived her efforts. In 2018, she received a Mandela Washington Fellowship, which took her to the United States to learn from medical professionals. There, she was also exposed to the workings of intensive care units at top hospitals.

In 2019, Crib A'Glow won USD50 000 in the Johnson & Johnson African Innovation Challenge 2.0, followed by the Unilever Young Entrepreneurs Award. With the growing recognition – and a better grasp of health regulations in Nigeria – Virtue began to experience success.

Scaling the business by coupling manufacturing and training

Today, Crib A'Glow is used in government and private hospitals as well as homes in more than 20 states across Nigeria. The device has also reached Ghana, Gambia and Kenya.

"We worked with healthcare providers to ensure compliance, and because Crib A'Glow runs on solar energy, it circumvents the problem of power cuts," says Virtue.

Originally designed for full-term infants, the LED phototherapy units have since been adapted to fit incubators, making them suitable for premature babies too. Each unit is built to work non-stop for 50 000 hours, after which the LED brightness diminishes to 70% and the bulbs need to be replaced.

Since 2017, over a million infants have been treated using Crib A'Glow. But Virtue's company, Tiny Hearts Technologies, doesn't stop at manufacturing the neonatal units. "We also train healthcare workers and parents, so they know how to identify jaundice," says Virtue. "It's critical to catch it early to avoid complications."

Social impact through healthcare partnership

Raising awareness is done through the Tiny Hearts' Yellow Alert Foundation, which empowers women with healthcare solutions.

Today, Tiny Hearts has around 12 full-time employees – the number fluctuates depending on production – and Crib A'Glow sales and rentals support the work of the Yellow Alert Foundation.

"Since 2020, the foundation has run without external funding," says Virtue. However, she would love to scale the business and expand its impact.

"We work with healthcare workers and the government. We can't do our work without them, especially if we want to reach rural communities, community health centres, and other stakeholders" she explains.

"Ultimately, we want to reduce the need to import basic medical devices and improve infant mortality statistics in Africa," says Virtue.

"This is what success looks like to us."