read time 5min

switch on

Climate Change

Sub-Saharan Africa makes up 80% of the global population that has no access to electricity, making the region central to the United Nations’ goal of expanding universal access to energy by 2030. In its Africa Energy Outlook 2022 report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) found that 600 million people in Africa do not have access to electricity. That’s 43% of the continent’s population, and that should be seen in the context of the International Monetary Fund’s estimate that power shortages and lack of energy access alone cost African countries between 2% and 4% of GDP.

Large, national-scale power grids may not be the answer. According to the IEA’s report, in rural areas – where more than 80% of the African citizens without access to electricity live – stand-alone and mini-grids remain the most viable solutions to promoting universal energy access.

Reaching Rural Communities

Africa’s rural and peri-urban areas are often too far from the main grid infrastructure. Public and private incentives to expand transmission lines are low, given that there is typically little, if any, industrial or corporate economic activity in these areas. Demand is also significantly lower than it is in urban settings.

By 2022, 11 million mini-grid systems, largely solar-powered, had been rolled out in sub-Saharan Africa. These, however, often need battery storage to make up for the intermittency of energy generation and require a hybrid mix of technologies to ensure that the lights stay on in the surrounding communities. A Chinese and Nigerian study published in Frontiers in Energy Research found that lead-acid batteries, which are cheaper to buy and install than lithium-ion batteries, make up 66% of Africa’s installed mini-grids.

According to World Bank data, more than 3 000 mini-grid facilities have already been installed in Africa, with a further 9 000 planned for development over the next few years.

The key to accelerating the development of these systems is effective government policies that allow and promote international and private-sector participation. Several countries are advancing policies that will create a conducive environment for the rollout of solar mini-grids. The results are already positive, with data released by the World Bank in September 2023 confirming that sub-Saharan Africa’s mini-grid projects have increased from just 500 in 2010 to about 5 000 today. The World Bank expects an additional 9 000 new projects to emerge in the coming years, powering at least 350 million more people in the region.

A Case Study

Connecting Kenya

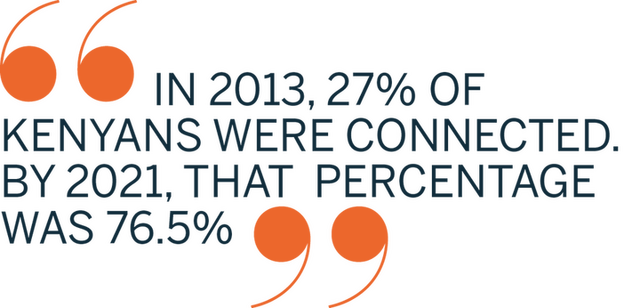

In 2008, Kenya’s then-president Mwai Kibaki launched Kenya Vision 2030, an ambitious plan to transform the country into a rapidly industrialising middle-income country by the year 2030. Part of that plan was to achieve universal access, where 95% of homes have access to electricity. By 2013, 27% of Kenyans were connected. By 2016, that percentage had increased to 55%. By 2021, it was 76.5%.

Mini-grids are helping to power that growth. In Kenya, a Rural Electrification Authority (REA) has been mandated to oversee and accelerate mini-grids in rural areas, mainly under a public-private partnership model. In this model, mini-grid customers pay a regulated tariff while the state power utility pays private companies who manage, develop and maintain the project over several years. The REA focuses on rural or peri-urban settings, where the national grid is not expected to be expanded any time soon.

In 2017 the World Bank approved USD150 million in finance to the Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access Project (KOSAP), with USD40 million of that geared towards developing mini-grids at 120 sites across the country. Ownership in Kenya’s case takes the form of public mini-grids, community-owned mini-grids and privately owned mini-grids. Mini-grid development is, however, dominated by the public sector. In community ownership models, communities have management models set up like a board that includes a manager and technical experts.

According to the World Bank analysis there are community-owned and -managed hydroelectric mini-grids in Thima, Kathamba and Kipini, which supply power to about 290 households, while a site at Tungu Kabiri supplies power to small businesses. Customers are then subject to tariffs.

Kenya’s public mini-grids are mixed sites with diesel, solar and wind generation. These customers pay the same tariffs as main grid customers, although it costs the public sector more to maintain their sites. The shortfalls are covered by subsidies. The mini-grids range from simple generation supply-centred sites to more sophisticated smart sites that can monitor consumption and have a host of other useful smart functions. These sites require upskilling, particularly when there is a community ownership model adopted at the site.

“Some mini-grid operators have diversified revenue streams, generating additional revenues from other business activities,” the World Bank analysis noted. “Power supply to customers is still the core business, but operators also provide additional services, such as setting up a small shop, distributing solar lanterns, phone charging, and electricity to provide services such as internet, printing, photocopying, water pumping, or agricultural processing.”

Elsewhere in Africa

In 2023 Senegal commissioned 60 solar-powered mini-grid sites in its southern Kolda region, with the Senegalese Rural Electrification Agency project targeting the provision of mini-grids to more than 300 villages by 2024. At the same time Ghana has used development grant finance to power 400 schools, 200 healthcare centres and 100 community service energy stations with mini-grid installations. The African Development Bank (AfDB) signed off USD28.49 million to achieve this. Similar projects are also under way in Niger, Tanzania and Madagascar.

Larger mini-grid installations that are set to power more than 230 000 households are attracting international private investment in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the government seeks to install a capacity of 35MW. Smaller projects are earmarked for three other regions.

In 2023 the United Nations Development Programme extended its mini-grid programme to Burkina Faso, in funding worth EUR1.6 million over four years, while in Nigeria a Rural Electrification Agency is set to add 51 hybrid mini-grid stations to its existing 12 solar-powered mini-grid installations in rural areas over the next few years.

Mini-grid installations are accelerating across Africa, with rapid expansion in some regions. The World Bank expects 12 000 more of these to emerge in different countries by 2030, but warns that these are only small steps towards solving a very big problem.

More than 160 000 mini-grids are needed to make a material and substantial dent in reducing electricity poverty among the other 380 million non-powered communities across Africa. There’s work yet to be done.

A Case Study

Connecting Kenya

In 2008, Kenya’s then-president Mwai Kibaki launched Kenya Vision 2030, an ambitious plan to transform the country into a rapidly industrialising middle-income country by the year 2030. Part of that plan was to achieve universal access, where 95% of homes have access to electricity. By 2013, 27% of Kenyans were connected. By 2016, that percentage had increased to 55%. By 2021, it was 76.5%.

Mini-grids are helping to power that growth. In Kenya, a Rural Electrification Authority (REA) has been mandated to oversee and accelerate mini-grids in rural areas, mainly under a public-private partnership model. In this model, mini-grid customers pay a regulated tariff while the state power utility pays private companies who manage, develop and maintain the project over several years. The REA focuses on rural or peri-urban settings, where the national grid is not expected to be expanded any time soon.

In 2017 the World Bank approved USD150 million in finance to the Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access Project (KOSAP), with USD40 million of that geared towards developing mini-grids at 120 sites across the country. Ownership in Kenya’s case takes the form of public mini-grids, community-owned mini-grids and privately owned mini-grids. Mini-grid development is, however, dominated by the public sector. In community ownership models, communities have management models set up like a board that includes a manager and technical experts.

According to the World Bank analysis there are community-owned and -managed hydroelectric mini-grids in Thima, Kathamba and Kipini, which supply power to about 290 households, while a site at Tungu Kabiri supplies power to small businesses. Customers are then subject to tariffs.

Kenya’s public mini-grids are mixed sites with diesel, solar and wind generation. These customers pay the same tariffs as main grid customers, although it costs the public sector more to maintain their sites. The shortfalls are covered by subsidies. The mini-grids range from simple generation supply-centred sites to more sophisticated smart sites that can monitor consumption and have a host of other useful smart functions. These sites require upskilling, particularly when there is a community ownership model adopted at the site.

“Some mini-grid operators have diversified revenue streams, generating additional revenues from other business activities,” the World Bank analysis noted. “Power supply to customers is still the core business, but operators also provide additional services, such as setting up a small shop, distributing solar lanterns, phone charging, and electricity to provide services such as internet, printing, photocopying, water pumping, or agricultural processing.”

Elsewhere in Africa

In 2023 Senegal commissioned 60 solar-powered mini-grid sites in its southern Kolda region, with the Senegalese Rural Electrification Agency project targeting the provision of mini-grids to more than 300 villages by 2024. At the same time Ghana has used development grant finance to power 400 schools, 200 healthcare centres and 100 community service energy stations with mini-grid installations. The African Development Bank (AfDB) signed off USD28.49 million to achieve this. Similar projects are also under way in Niger, Tanzania and Madagascar.

Larger mini-grid installations that are set to power more than 230 000 households are attracting international private investment in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the government seeks to install a capacity of 35MW. Smaller projects are earmarked for three other regions.

In 2023 the United Nations Development Programme extended its mini-grid programme to Burkina Faso, in funding worth EUR1.6 million over four years, while in Nigeria a Rural Electrification Agency is set to add 51 hybrid mini-grid stations to its existing 12 solar-powered mini-grid installations in rural areas over the next few years.

Mini-grid installations are accelerating across Africa, with rapid expansion in some regions. The World Bank expects 12 000 more of these to emerge in different countries by 2030, but warns that these are only small steps towards solving a very big problem.

More than 160 000 mini-grids are needed to make a material and substantial dent in reducing electricity poverty among the other 380 million non-powered communities across Africa. There’s work yet to be done.

TEXT: Tunicia Phillips